1920s

Childhood and

Teenage Years

Max Ferdinand Perutz was born in Vienna on May 19th, 1914. Both his parents, Hugo Perutz and Dely Goldschmidt, came from families of textile manufacturers who had made their fortune in the 19th century by the introduction of mechanical spinning and weaving into the Austrian monarchy.

Max Perutz was first educated at the Theresianum, a grammar school derived from an officers’ academy from the days of the Empress Maria Theresia. Many years later he said:“I owe my first step to popularity to scarlet fever which I caught when I was fourteen. To disinfect the classroom, my schoolmates got three days off, for which they thanked me solemnly in a letter signed by the entire class”.

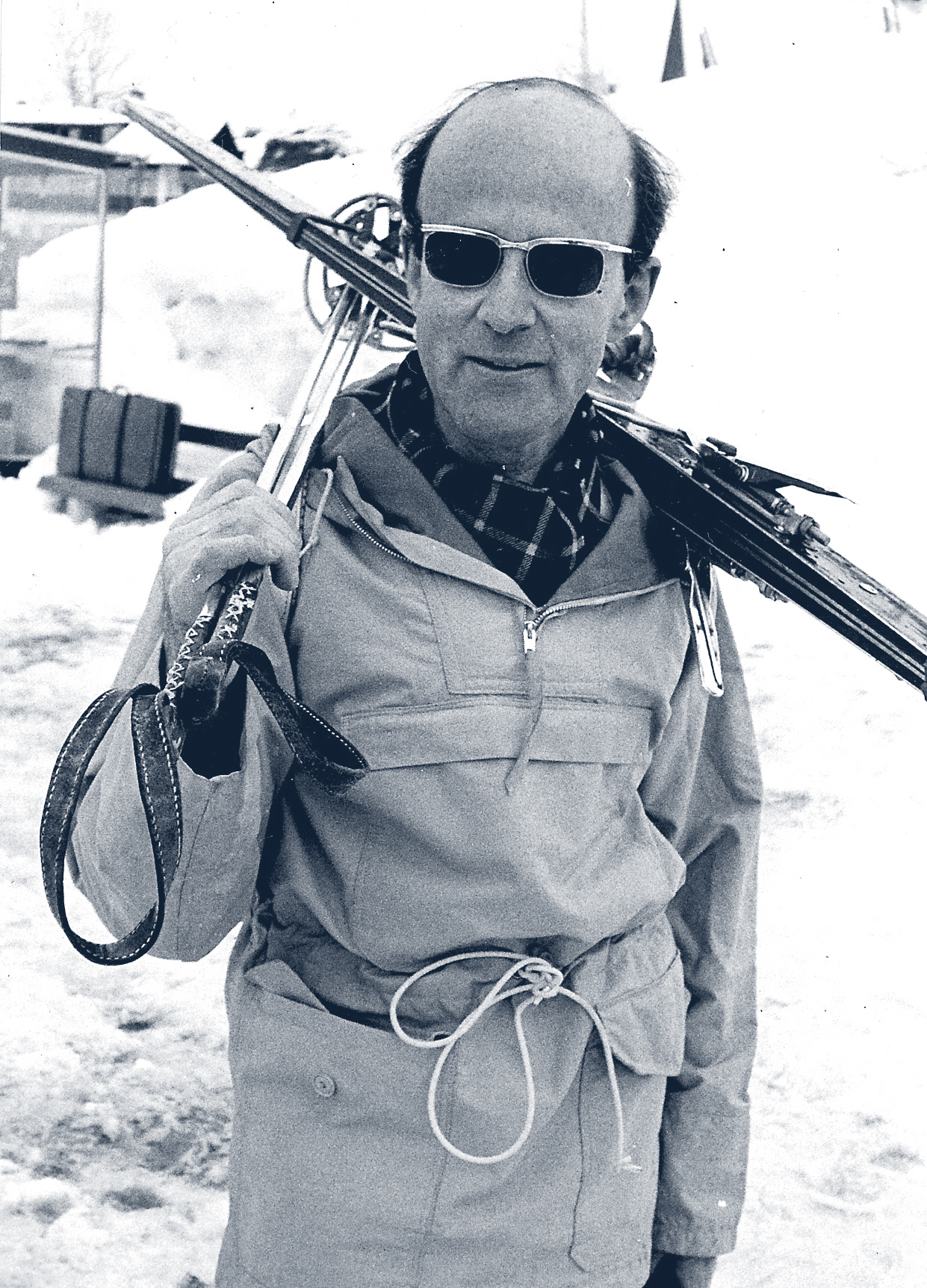

At sixteen, Max won the cup for his school in the skiing competition of the Vienna High Schools, and as a result of that victory his standing at school was transformed.

“For the first time in my life I was treated with a certain degree of respect. From then on our gym teacher always gave me top marks, but they happened to be the only ones in my otherwise mediocre school reports”.

Max aged seven, with his older siblings Franz and Lotte, in Reichenau

Pupil at the Theresianum, aged fifteen

Max aged about two, with his Bavarian nanny Cilly Jetzfellner

Max was supposed to study law in preparation for entering the family business. However, a good schoolmaster at the Theresianum kindled his interest in chemistry, and he made this the subject of his studies at university.

Although largely disappointed with the way in which the subject was taught, he acquired a special interest in organic biochemistry, having heard about the work of the Nobel Prize winner (and discoverer of vitamins) Sir Gowland Hopkins at Cambridge.

His teacher, Herman Mark, visited Cambridge with plans to pave the way for Perutz to join Hopkins’ group. But Mark met J. D. Bernal, who said that he would take Perutz as his student.

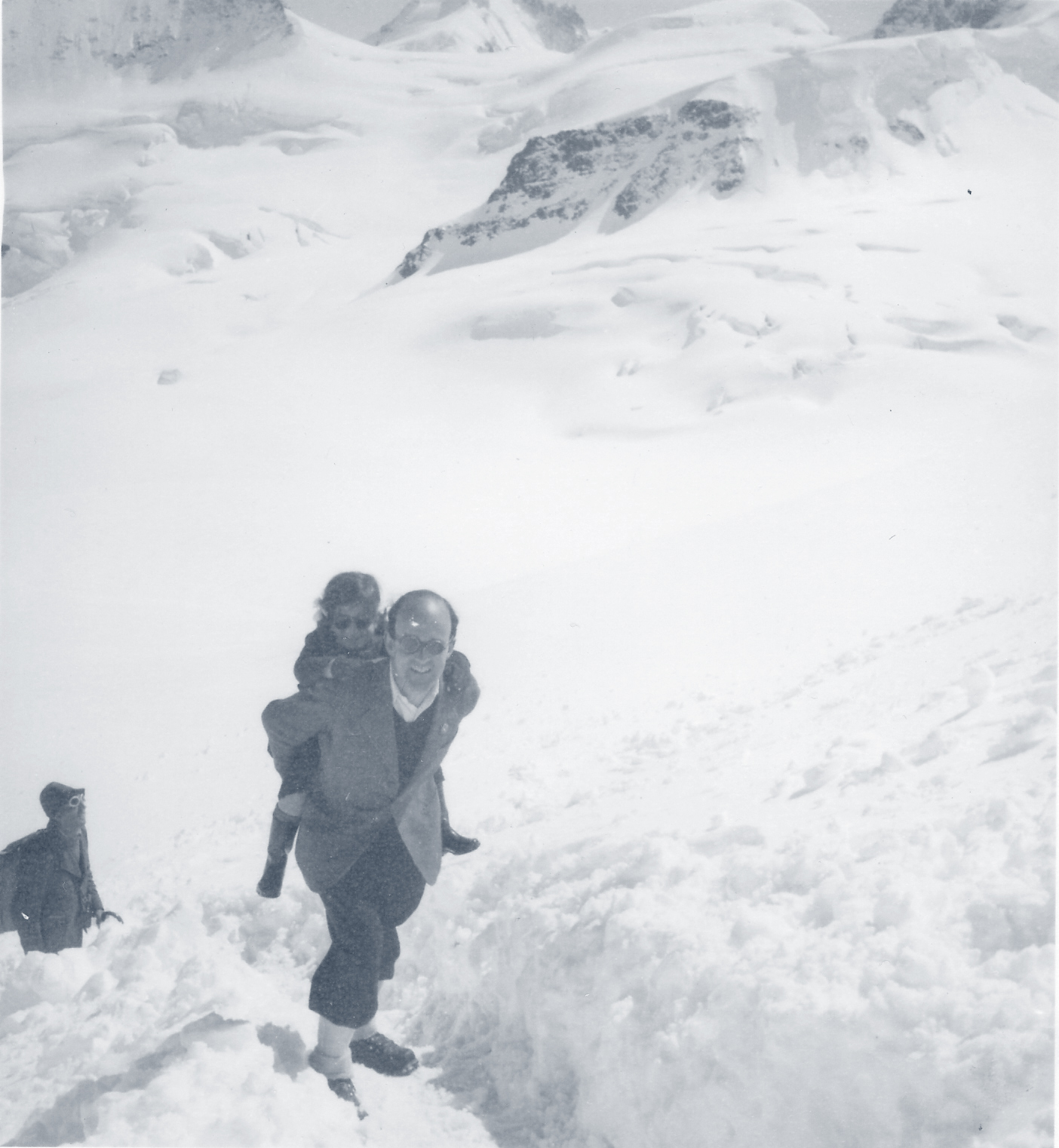

Max Perutz with his three year-old daughter Vivien during the 1948 Jungfraujoch expedition.

Max Perutz with his three year-old daughter Vivien during the 1948 Jungfraujoch expedition.